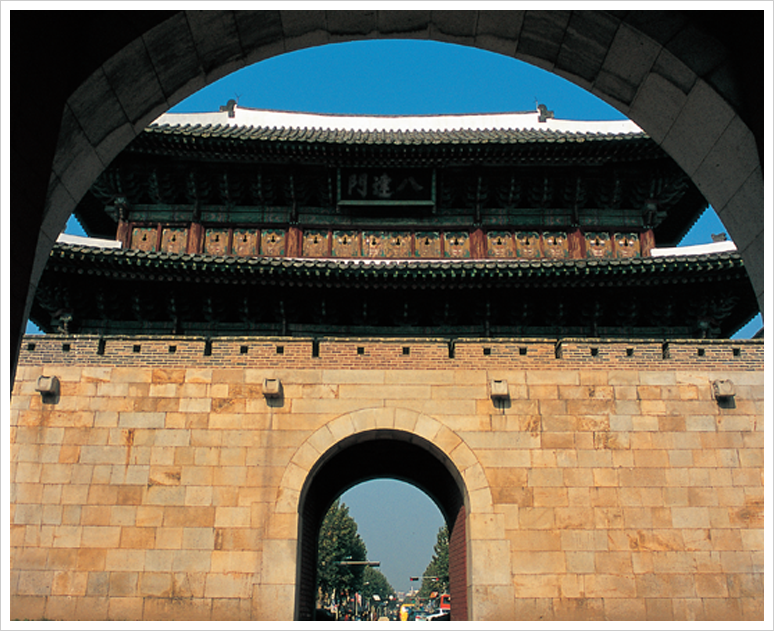

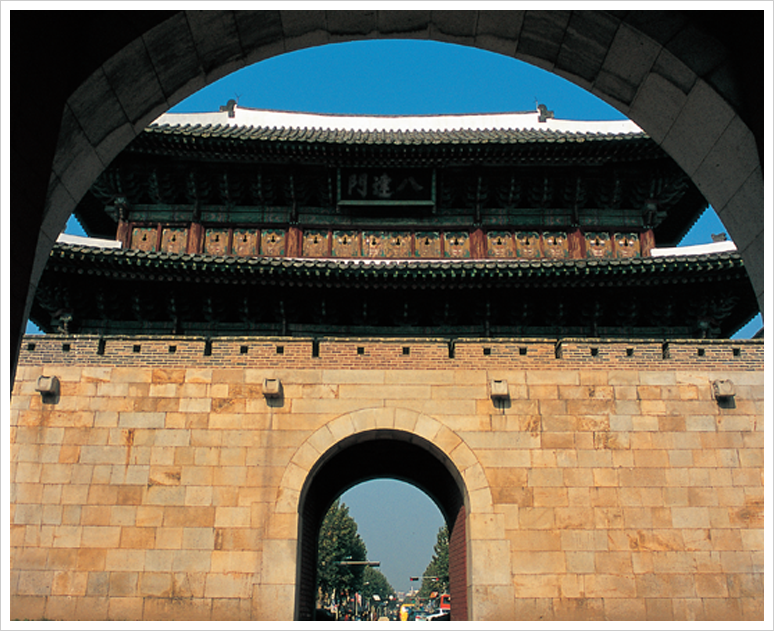

Paldalmun Gate (Treasure

No. 402) is the south gate of

Hwaseong Fortress, taking its

name from the mountain to its

west, Mt. Paldalsan.

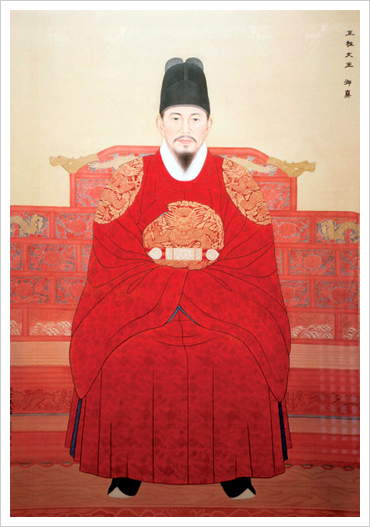

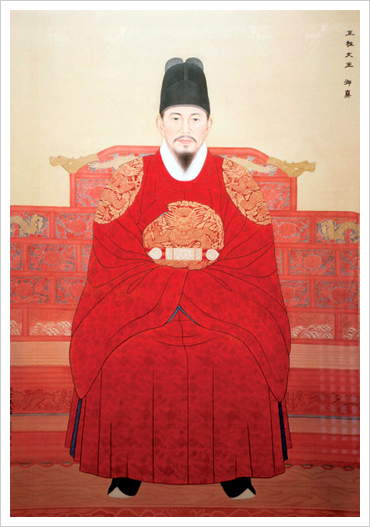

As an 11-year-old boy, Great

King Jeongjo succeeded his

grandfather, King Yeongjo,

becoming the 22nd monarch

of Joseon.

Born out of Adversity

A hero does not live for himself, but sacrifices himself for others. When

he is the ruler, we call him a “great king” and strive to emulate his lessons.

Throughout Korean history,

there are four monarchs who have come to

be called great kings: Great King Munmu, the 30th ruler of Silla, who

achieved the unification of Korea; Great King Gwanggaeto, the 19th

ruler of Goguryeo, who recovered the Liaodong Peninsula and expanded

the kingdom’s territory; Great King Sejong, the 4th ruler of Joseon, who

invented the Korean alphabet, Hangeul; and the 22nd monarch of Joseon

(1392–1910), Great King Jeongjo (r. 1776–1800), who can be regarded as a

mentor for enlightened governance for the contemporary generation.

Named Yi San (adult name Hyeongun; pen name Hongjae), King Jeongjo was

born to Crown Prince Sado and Lady Hyegyeong. As a child, he witnessed his

father’s tragic death—an unjust death, locked inside a rice chest—and realized

that chronic conflicts between different political factions were what put his

father to death. This is why he made life-long endeavors to mind his words and

acts. Striving to sharpen judgment through indirect experience from reading

the classics, King Jeongjo protected himself from political turbulence. He took

every caution in dealing with people and never stopped making efforts to be

agile both mentally and physically.

Construction of Hwaseong Fortress

Succeeding his grandfather to the throne, King Jeongjo posthumously promoted

Crown Prince Sado to Crown Prince Jangheon and moved his tomb to Mt.

Hwasan in Suwon, which was considered the most propitious site at the time

according to geomantic principles. The king also ordered the construction of

Hwaseong Fortress in Suwon, which was inscribed on the World Heritage List

in 1997.

King Jeongjo had several reasons in mind when he embarked

on the construction of Hwaseong Fortress. He wished to

put an end to political partisanship and to usher in an era of

political innovation by building a new seat of power in the

fortress. Easy access to the transferred site of his father’s tomb,

Yungneung, was also one of the reasons. But what propelled the

king the most was his desire to strengthen royal power. Capital

politics had been dominated by the political faction

backed by

powerful merchants; therefore, the king wished to build a new

commercial stronghold in Hwaseong, a traffic hub which could

be easily accessed from any direction. After granting

the administrative district of Hwaseong the same high

status as the capital and dispatching the royal guard

Jangyongyeong, King Jeongjo started the construction

of Hwaseong Fortress in 1794. He entrusted the

design of the fortress to Jeong Yak-yong, a scholar

from the school of silhak, or practical learning. Jeong

reviewed advantages and disadvantages of the existing

fortifications both in Korea and in China and referred

to a comprehensive list of books and documents, coming up with novel, unconventional

construction strategies. He suggested every detail needed including building methods,

varieties and forms of facilities, and siting of fortress structures, in order to ensure

the best possible capacity for both defense and attack. The general supervisor for the

construction was Chae Je-gong; the field manager Jo Sim-tae.

Principles of Construction

King Jeongjo set down his primary principles to guide the construction of Hwaseong

Fortress: first, be slow; second, be modest; and third, be strong. He emphasized that

fortress should not be built in haste and not be made splendid, and must be based

on a solid foundation. The king also cared about the welfare of workers who were

mobilized for the construction. People were scrupulously paid wages for their labor,

and it is recorded that those who worked only half a day also received money. Laborers

were ordered to take days off when it was too hot or too cold. To encourage them, the

king used to give them gifts of alcohol and snacks. He also gave away fans and hats for

protection against heat and sun and invigorating medicines on hot summer days. These

measures were an innovative practice at that time, when people mobilized for state

construction were callously treated and never dreamed of paid labor.

Hwaseong Fortress (Historic

Site No. 3) has Mt. Paldalsan

to the west and a gentle hill to

the east. Construction of the

fortress started in 1794 and

was completed two years later

in 1796 during the reign of

Great King Jeongjo.

What is notable is that laborers were granted not only rights but also given duties and

responsibilities. For each construction area, information on who did what and who was

responsible for supervision was marked on stone, so that the person in charge faced due

punishment for problems with the construction.

Western technology and knowledge were benchmarked for the construction of

Hwaseong Fortress; equipment for lifting and transferring heavy materials was invented,

helping reduce the days needed for construction. The most important material, stone,

was quarried from the adjacent mountain Sukjisan; roof tiles and bricks were produced

in a kiln built near the construction site; and timber mostly came from Anmyeondo

Island on the western coast of the Korean Peninsula and some from Gangwon-do

Province in the north.

Hwaseomun Gate (Treasure

No. 403) is the west gate

of Hwaseong Fortress with

a semicircular defensive

outwork.

The City for People

The name

Hwaseong was given by King Jeongjo after

viewing the site from an overlook on Mt. Paldalsan in

January 1794, the 18th year of his reign. Construction

of Hwaseong Fortress began in February that year and

was completed in September 1796. The fortification is

5.74 kilometers long and 5–6 meters high. Combining

to form a single defensive structure, various facilities

of the fortress came in diverse forms with various

functions.

Driven by his passion to establish a secure and safe

city, King Jeongjo took another innovative measure: an attempt to establish a selfsufficient

city. State-run paddy fields called

dunjeon were created in the vicinity of the

fortress to supply rice to those residing in the fortress. To provide water to irrigate

the fields, reservoirs were built to the west and to the south of the fortress, named

Chukmanje and Mannyeonje.

It is recorded that a reservoir was made to the east of

the fortress as well, but its site has not been confirmed. This may explain why Korea’s

Rural Development Administration had been long based in Suwon until recently.

King Jeongjo was known to directly take care of ordinary people’s concerns: people

lined the street where the king passed on his visits to his father’s tomb in order to

speak to him about their personal concerns, and the king listened and addressed

them.

In 1801

Hwaseong seongyeok uigwe (

Royal Protocol on the Construction of Hwaseong

Fortress) was compiled. Encompassing details on the construction plan, methods,

and equipment, personal details on laborers, salary calculation methods, budget, the

sources and uses of materials, and methods of processing materials. These records

serve as a milestone in architectural history and have intrinsic historical value.

Recognition was given by UNESCO when the royal protocols of Joseon including

the volume on the construction of Hwaseong were registered in the Memory of

the World in July 2007. The fortress itself was inscribed on UNESCO’s World

Heritage List in December 1997 and

has been under national management

as Historic Site No. 3. Paldalmun Gate

and Hwaseomun Gate, the south and

west entrances of to the fortress, are also

designated National Treasure No. 402

and National Treasure No. 403.