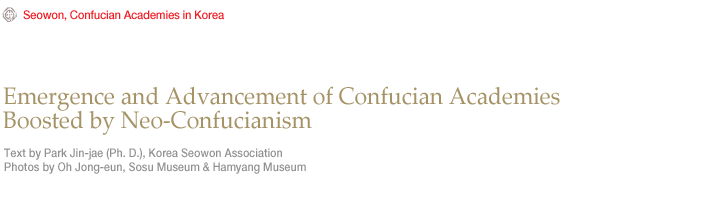

Sosuseowondo (Picture of Sosu Seowon ).

Emergence of Confucian Academies

Seowon, private Confucian academies, first appeared during the early Joseon period,

established and championed by the rural literati, or sarim, a term that means, literally,

“a group of scholars.” Sarim were a new social and political force that emerged as a

foil to the entrenched power of the learned nobility, or sadaebu, who played a leading

role in the establishment of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910). Sadaebu scholars came

into important positions in the central government through the state examination

system towards the latter part of the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392). Although they

professed to follow the lofty ideal of valuing both intellectual achievement and good

governance, sadaebu started to abuse their power, fomenting political conflicts and

breeding corruption after ushering in the new dynasty of Joseon.

The sarim, which was a faction of the sadaebu, were steeped in the same scholarly

tradition of Neo-Confucianism, but soon found themselves at odds with the

establishment’s learned nobility. They retreated to the rural areas after the founding

of the Joseon Dynasty and focused on enhancing academic capacity and nurturing

new generations of scholars. The rural literati as a social group were not based on

hereditary titles but on individual capacities.

The failure of the local education system also created an environment conducive to

the emergence of seowon. Driven by the need to produce bureaucrats, the royal court

of Joseon established central and local educational institutions. But the local schools,

hyanggyo, were dysfunctional, bogged down by teachers and curricula lacking in

quality and substance. Alternative educational institutions based in rural areas were

sorely needed. Under these circumstances, seowon filled the educational void, led by

the rural literati who pursued a more liberal and at the same time in-depth study of

Neo-Confucianism as the foundation of education.

The ritual space (Daeseongjeon Shrine) was positioned in front, and the educational space (Myeongnyundang Lecture Hall) at back in Seonggyungwan

Simwonnok (Records of Visitors) of Sosu Seowon,containing guests’ names and visiting dates.

Advancement of Confucian Academies

The role of seowon expanded alongside the rise of the sarim’s political

influence. As the rural literati grew into a major political force, seowon as

their academic bases developed into strongholds for social and political

activities. In the archives of seowontoday are found visitors’ books

containing brief personal information on guests, which show that scholars

who visited seowon came not only from the vicinity but also from far-flung

areas. Scholars from various regions assembled in seowon and solidified

social bonds; thus these local Confucian academies became lively centers

for social and cultural activities.

Sosu Seowon lies to the south

of Mt. Sobaeksan between

Yeonggwibong Peak and

Yeonhwabong Peak.

History of Confucian Academies

The first seowon was built in 1543 by Ju Se-bung, the magistrate of Punggi, to honor

the prominent scholar An Hyang (1243–1306), who introduced Neo-Confucianism

from China in the late Goryeo period. Ju built Munseongsa Shrine in 1542 on the

old site of Susuksa Temple in An’s hometown, Sunheung, Gyeongsang-do Province.

The following year he constructed a separate structure next to it as a study space;

together they were called Baegundong

Seowon. Baegundong Seowon was built

to complement the function of the state

local education system. Later it became

the first royally authorized seowon. In 1550,

King Myeongjong bestowed to it a nameplate

carved with the new name

Sosu Seowon in the king’s

handwriting, upon the request of Yi Hwang (1501–1570),

who was the foremost Neo-Confucian philosopher of the

time.

Munseonggongmyo Shrine

at Sosu Seowon houses

spirit tablets for An Hyang and

Ju Se-bung.

The development of private Confucian academies

in Korea are divided into three stages: emergence

in the 16th century, development in the 17th

century, and decline after the 18th century.

During the emergence stage, seowon

gained recognition from the state as

educational institutions and solidified their

capacity, laying the foundation for future

development. Sosu Seowon was the first to

be endowed with a new name from the king

during this period, followed by Imgo Seowon

in Yeongcheon (1554), Namgye Seowon in Hamyang (1566), Oksan Seowon in

Gyeongju (1574), Sungyang Seowon in Kaesong (1575), and Dosan Seowon in

Andong (1575). A rich trove of historical materials provide detailed records on the

organization and operation of local Confucian academies during this period.

A procession makes its way to

Dosan Seowon for the reenactment

of dosan byeolgwa, a

special government examination to select officials.

The development stage saw seowon multiply in number and spread throughout

the country. Private Confucian academies began to spring up in the southeastern

province of Gyeongsang-do, and then expanded to the southwestern and middle

sections of the country and to the northern province of Hamkyong-do. During this

period, a number of shrines commemorating Confucian sages were constructed

under the different title

sau, which was not distinct from seowon in their purposes

and functions. The number of seowon peaked to about 900 towards the latter Joseon

era, resulting in natural side-effects of rapid expansion: deterioration in quality of

education at local academies accompanied by social and political problems as the

sarim suffered reversal of fortunes.

A restriction was imposed by the state on the construction of private academies in

the 18th century, and some existing ones were torn down. Confucian academies

continued to be built irrespective of the significance of the sage to be honored or

of educational purposes.

The restriction culminated in a blanket closure in 1871

when all the seowon throughout the country, except for 47, were abolished based on

the “one seowon for one sage” principle under orders from the royal regent Prince

Heungseon (1820–1898).

Spiritual Legacies of Confucian Academies

Although many private Confucian academies were demolished, their spiritual

legacies still bear implications for the modern world. Seowon were the space where

competent scholars of character were nurtured during the Joseon Dynasty and those

that survived, or had been revived, continue to serve as the bailiwick of education

founded on ethics and morals in the present day.

Seowon’s educational focus on nurturing character and personal virtue in addition

to academic capacity fosters precious spiritual values for contemporary and future

generations. In the 1900s, private Confucian academies demolished in the late

19th century started to be restored, and there are currently are about 640 of them

throughout the country. Confucian academies are striving to revive and reinterpret

the philosophical principles and teachings of the Confucian sages.

As the embodiment of the Confucian cosmology, seowon were not only educational

institutions and ritual places but also were the center of a community operating diverse

activities in such areas as publishing, arts, and politics, where scholars gathered together

and raised public voices. For these reasons, seowon are a significant part of Korea’s

tangible and intangible legacies, which have to be protected and transmitted well into

the future.